GUREME Raymond

Chemin de la Résistance et des Maquis

Mis en ligne sur le site le 17 avril 2020 / mise à jour 8 juillet 2024

Liens utiles :

liberation.fr/debats/2020/05/28/la-place-de-raymond-gureme-est-au- pantheon_1789654?utm_medium=Social&utm_source=Facebook&fbclid=IwAR00rWppXp6n2nErU4bXpxehTK RhdPIgtEdeco3tvTAVq1J5MFH-cLHr_yM#Echobox=1590689775

https://www.franceculture.fr/emissions/une-histoire-particuliere-un-recit-documentaire-en-deux-parties/resistances-tsiganes-12-raymond-gureme

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raymond_Gur%C3%AAme

https://www.ladepeche.fr/article/2010/04/04/810550-blessures-enfouies-tsigane-francais-interne-1940-france.html

http://www.forgottencosmopolitans.eu/?p=584

https://www.google.com/search?source=univ&tbm=isch&q=Raymond+GUR%C3%8AME&client=firefox-b-d&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjHoq7Lpd7pAhXlz4UKHXjrBMEQsAR6BAgJEAE#imgrc=Tu64vGBtLLG7jM

Yann DANIEL nous propose un article de Libération sur un déporté/résistant Raymond GURÊME décédé à l'âge de 94 ans; cet homme ,ultime témoin de l’internement des «nomades» par l’Etat français, mérite qu'il soit connu.

Photo Bertrand Guay. AFP

LIBERATION - 28 mai 2020

Raymond Gurême en mars 2010.

Figure du peuple des voyageurs et de la

Résistance, ultime témoin de l’internement des «nomades» par l’Etat français, Raymond Gurême est mort dimanche à l'âge de 94 ans.

https://www.liberation.fr/debats/2020/05/28/la-place-de-raymond-gureme-est-au-pantheon_1789654

*téléchargez l'article

Tribune. Raymond Gurême est mort. Une profonde émotion m’étreint en écrivant ces mots. Cette nouvelle apparaît presque irréelle tant Raymond a toujours incarné la vitalité et l’exigence de révolte aux yeux de toutes celles et tous ceux qui ont la chance de le connaître et de l’aimer. Raymond n’a rien d’un vieillard mais tout d’un Gavroche circassien, lui qui avait fait ses débuts à l’âge de 2 ans sur la scène du cirque familial, lequel faisait aussi et surtout office de cinéma ambulant. C’était le temps de l’insouciance avant celui des épreuves. La vie de Raymond a définitivement basculé le 4 octobre 1940, lorsqu’il a été arrêté par des policiers français et enfermé avec sa famille dans plusieurs camps d’internement.

A l’âge de 94 ans, il a toujours gardé l’ardeur et la vivacité, tant intellectuelle que physique, de ses 15 ans de 1940. Pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, il se sera évadé dix fois avant de rejoindre les rangs de la Résistance. Raymond est de la génération de ceux qui ont eu 20 ans au moment de la Libération, mais il lui faudra quelques années encore après la fin du conflit pour retrouver la trace des siens. Comme beaucoup de «nomades», lui et sa famille ont alors tout perdu et n’ont jamais été indemnisés, même avec de ces belles paroles dont usent les gouvernants pour envelopper leurs mauvaises actions ou leurs lâches abstentions. Il n’en gardait nulle amertume mais a toujours été mû par l’ardent désir de témoigner pour rappeler les persécutions du passé et, dans un même mouvement, d’agir pour combattre les injustices du présent.

La flamme de la Résistance

Son indignation face à toutes les formes de misère est toute entière résistance lorsqu’il exhorte de plus jeunes que lui à toujours rester debout, une de ses expressions favorites. Toutes celles et ceux qui l’ont connu et aimé sont marqués à vie par cette force de conviction. Il est un symbole vivant pour des milliers de jeunes Roms, Sinté, Kalé, Yéniches et voyageurs de l’Europe entière. Pour moi, Raymond est tout à la fois le grand-père que je n’ai pas connu et le frère que je n’ai pas eu. Dans toute ma vie, j’ai rencontré cinq personnes en qui brillait avec une telle intensité la flamme de la Résistance. Les quatre autres sont Georges Guingouin, Marie-Rose Gineste, Soha Bechara et Pinar Selek.

Plus que quiconque, Raymond Gurême incarne les souffrances et les combats du peuple des voyageurs, profondément inscrits dans l’histoire de la France et de l’Europe. Il est le dernier survivant et l’ultime témoin de l’internement des «nomades» par l’Etat français, une tragédie trop longtemps occultée et encore largement méconnue. Rappelons, en outre, pour ceux qui l’auraient oublié – ou ne l’auraient jamais su –, que c’est la IIIe République finissante qui a, par un décret du 6 avril 1940, interdit la circulation des «nomades». Rappelons encore que le dernier camp d’internement a été fermé en juin 1946, soit près de deux ans après la Libération. N’oublions pas que les persécutions avaient débuté bien avant le

génocide nazi et n’ont jamais cessé. Pour s’en tenir à l’exemple de la France, la continuité est frappante et terrible entre le recensement de 1895, la mise en place du carnet anthropométrique en 1912, son remplacement par des carnets de circulation en 1969 et la persistance en 2020 du statut administratif des «gens du voyage» sur une base raciale. Il est temps de combattre sans concession l’antitziganisme sous

toutes ses formes, notamment institutionnelles.

En reconnaissance de son action depuis quatre-vingts ans, la place de Raymond Gurême est au Panthéon. Mais elle est aussi et avant tout dans nos cœurs, à nous qui l’aimons et l’admirons, sa famille, ses amis, voyageurs et gadjé unis dans la perpétuation d’un même idéal de Résistance.

Henri Braun avocat au Barreau de Paris

Source :

http://www.forgottencosmopolitans.eu/?p=584

The Gurême family in 1937, courtesy of Raymond Gurême

From circus acrobat to Resistance fighter: the story of Raymond Gurême

Posted on November 25, 2019 Author adminComments Off on From circus acrobat to Resistance fighter: the story of Raymond Gurême 3049 Views

Raymond Gurême was born in 1925 near Paris into a French Manouche (i.e. Sinti in French) family. As did several generations of the family before them, his parents owned a small circus and a travelling cinema: the family toured France and parts of Belgium and Switzerland where they were warmly received in villages deprived of entertainment. The whole family was involved: Raymond’s father Hubert Leroux, a First World War veteran, was an acrobat, musician and film projectionist, his mother Mélanie trained their nine children who all mastered different circus activities. Raymond for instance was an acrobat, a clown and later a horse tamer. He recalls the fun but also the hard work, such as rewinding films onto their reels after the evening screenings.

At that time, in France, many so-called “Nomadic” families ran small circuses and travelled mainly through the rural areas (see also the histories of the Esther http://www.forgottencosmopolitans.eu/?p=447 and Sénéca families http://www.forgottencosmopolitans.eu/?p=211).

The Gurême family in 1937, courtesy of Raymond Gurême

In an increasingly hostile environment, however, the “Nomadic” lifestyle was considered a threat. French authorities had already controlled the movements of all travelling groups since 1912, but circulation was forbidden from 6 April 1940, in the context of the Second World War.

Internment and war-time events

In 1940, the Gurême family was staying in Petit-Couronne, near Rouen. In early October 1940, the family was arrested by French police and interned in the Darnétal camp, one of the camps for “Nomadic” families. Two months later, they were transferred – by train and on foot – to Linas-Montlhéry, a much bigger camp for “Nomads” which was situated on a disused motor racetrack in the south of Paris.

In his book Interdit aux Nomades, published in 2011 (co-authored by Isabelle Ligner), Gurême describes the terrible living conditions: food was scarce, hygiene was impossible, inmates had to sleep on the wooden floors of the unheated barracks. Raymond escaped the camp a first time with his brother: they tried to get their birth certificates to prove that they were French but were arrested following a denunciation by a mayor. Sometime later, Raymond tried again and succeeded. He could work as a farmhand in Brittany and managed to get to Linas-Montlhéry from time to time to supply his still-interned family with food. In April 1942, the camp of Linas was closed and all inmates, including the Gurême family, were transferred, first to the camp of Mulsanne, then to Montreuil-Bellay, the biggest internment camp for “Nomads” in occupied France.

In August 1943, Raymond was arrested by the police for having stolen German food supplies and sent to forced labour camps, first in Heddernheim, then in Oberursel, both near Frankfurt in Germany. In June 1944 he managed to escape and to return to France where he decided to make contact with the Resistance. He joined the French Forces of the Interior (FFI) because he felt that he had not fought enough. His unit, posted in the North of Paris, was in charge of sabotage actions, in particular of German arms, transport and tanks. Between 19 and 25 August 1944, he actively participated in the Liberation of Paris but, as is the case for other resistance-fighters from the travelling community, his role was never fully acknowledged.

The hardships of the post-war period

After the war, Raymond Gurême had no trace of his family and feared they had not survived. But in 1950, a Belgian member of the travelling community told him that his parents and several siblings were in Belgium so he immediately got on a bike to join them.

He learned that his parents had been liberated in 1943. His father had thereupon returned to Darnétal in order to claim his personal and professional possessions, from the family caravan to the circus tent and the cinema equipment. However, everything had “vanished” and he was unable to retrieve anything. For the Gurême family, as for many other “Nomadic” families in the travelling circus business, this meant a considerable social and financial decline from which the family would never recover. Therefore, when they returned to France, they had to move from farm to farm and work on the fields.

During that time, Raymond met and married Pauline, a young woman from an Alsatian Yenish family of basket-weavers. She had been interned herself for three months, with other family members, in the Jargeau camp. Raymond and his wife raised 15 children and worked as scrap dealers, market vendors and migrant farm workers. In the 1980s, he could finally afford to reconnect with his passion for horses: he bought several ponies and toured village fairs with his pony ride.

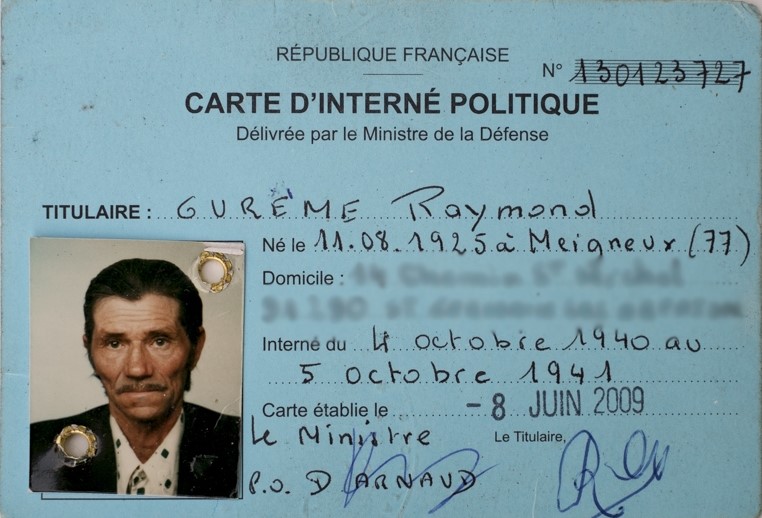

He only learned in 1976, thanks to a volunteer organization helping Sinti and Roma, that he was entitled to the status of political internee but would only actually be recognized as such in 2009.

After many years of travelling, in the late 1960s, Raymond Gurême chose to live with his family on a plot of land opposite the former camp of Linas-Montlhéry. He explains this decision first and foremost by claiming that it is right there that he can feel the presence of his parents. But he also considers his installation as an act of defiance: near the exact spot where he and so many other “Nomads” were interned, he is today the head of a 200-strong family.

A mission to speak out about the past

Like many other former camp inmates, Raymond did not speak about his own war-time experiences and the persecution in general of so called “Nomads” in France for several decades. But in 2004, at an event organized by a Travellers’ association, he publicly recalled his internment for the first time and has since become one of the most important witnesses of the war-time persecution of Sinti and Roma, speaking in schools and public events throughout the country. His story played an important role in the recognition and awareness of the “Nomads’” fate in 20th century France.

Raymond Gurême has taken on this responsibility and in 2010 has created the Collectif pour la commémoration de l’internement des Tsiganes et Gens du voyage au camp de Linas-Montlhéry (association for the commemoration of the internment of ‘Gypsies’ and Travellers at the Linas-Montlhéry camp). Every 27 November, date of the Linas camp opening, the Collectif organizes a remembrance march near the site of the former camp, followed by a ceremony and a reunion at the Gurême’s residence.

Photo of the annual remembrance march to Linas-Montlhéry

After the publication of Interdit aux Nomades, he was appointed Chevalier des Arts et Lettres by the French Minister of Culture in 2012. This Order of France medal was awarded to him for his contribution to the struggle against the discriminations Sinti and Roma still have to endure today – and from which he and his family are not exempt.

Raymond Gurême with his « Forbidden for Nomads » sign, which he placed at the entrance of his grounds, courtesy of Jean-Baptiste Pellerin

Raymond in the words of his friend François Lacroix, founder of the Collective which upholds the memories of the internment in the Linas-Montlhéry camp:

“Raymond, soon 95 years old. An ascetic body, in memory of the violence and the suffering of the past.

A last witness. Since the first words he shared about his family and personal trauma, a strong will to talk about it: the internment in France, wanted by the French government, in the Linas-Montlhéry camp, near Paris.

Remembering, but for today. Remembering the inexpressible, but to liberate today, to go beyond social and identity constraints… In order to be free, sometimes you have to escape, often you have to denounce, many times you have to be brave, always you have to resist. To be free you also have to, and above all, be able to dance, to celebrate, to love and protect people in need: poor, migrants, all the women and men that have just a phone booth to sleep… Raymond’s life today. Soon 95 years old.”

Authors: Bruna Lo Biundo and Sandra Nagel; Past/Not Past, https://pastnotpast.com/

Sources:

Ils ont eu la graisse, ils n’auront pas la peau, film by Jean-Baptiste Pellerin on Raymond Gurême’s life, 2013 https://vimeo.com/80358019

Radio broadcast Une histoire particulière : Résistances Tsiganes. Raymond Gurême, France Culture, 8 September 2018 https://www.franceculture.fr/emissions/une-histoire-particuliere-un-recit-documentaire-en-deux-parties/resistances-tsiganes-12-raymond-gureme

Raymond Gurême avec Isabelle Ligner, Interdit aux Nomades, Calmann-Lévy, 2011

Isabelle Ligner, « Raymond Gurême, l’homme révolté », Blog Mediapart, 21 August 2013 https://blogs.mediapart.fr/infofestival-douarnenezcom/blog/210813/raymond-gureme-lhomme-revolte

Lise Foisneau, Valentin Merlin. “French Nomads’ Resistance (1939-1946)”. Angela Kóczé and Anna Lujza Szász (ed.), Roma Resistance during the Holocaust and in its Aftermath. Collection of Working Papers, Budapest, Tom Lantos Institute, p. 57-101., 2018. ⟨halshs-01884555⟩

Archives départementales des Yvelines, cotes 300 W 81